Northumberland-born painter John Martin (1789-1854) is best-known as a painter of religious subjects and fantastically apocalyptic panoramic compositions like the one below. He often combined the two genres into vast landscapes, peopled with a myriad of tiny, overwhelmed figures. He enjoyed great success in early Victorian England, taking his hugely popular canvases on nationwide tours which drew large, admiring crowds, eager to be instructed and overawed in equal measure. You can learn more about Martin’s work and career in this Tate Shot.

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (c.1555) is an oil painting attributed to Pieter Bruegel the Elder. It purports to be about the Greek mythological figure, Icarus, plunging into the sea, after melting his waxy wings, by flying too close to the sun. But the composition is actually dominated by the mundane earth-bound activities of ploughmen, shepherds and traders with the eponymous aviator apparently merely a small sideshow in the lower right-hand corner. Icarus is often used as a metaphor for the errors of overweening human pride, vanity and ambition.

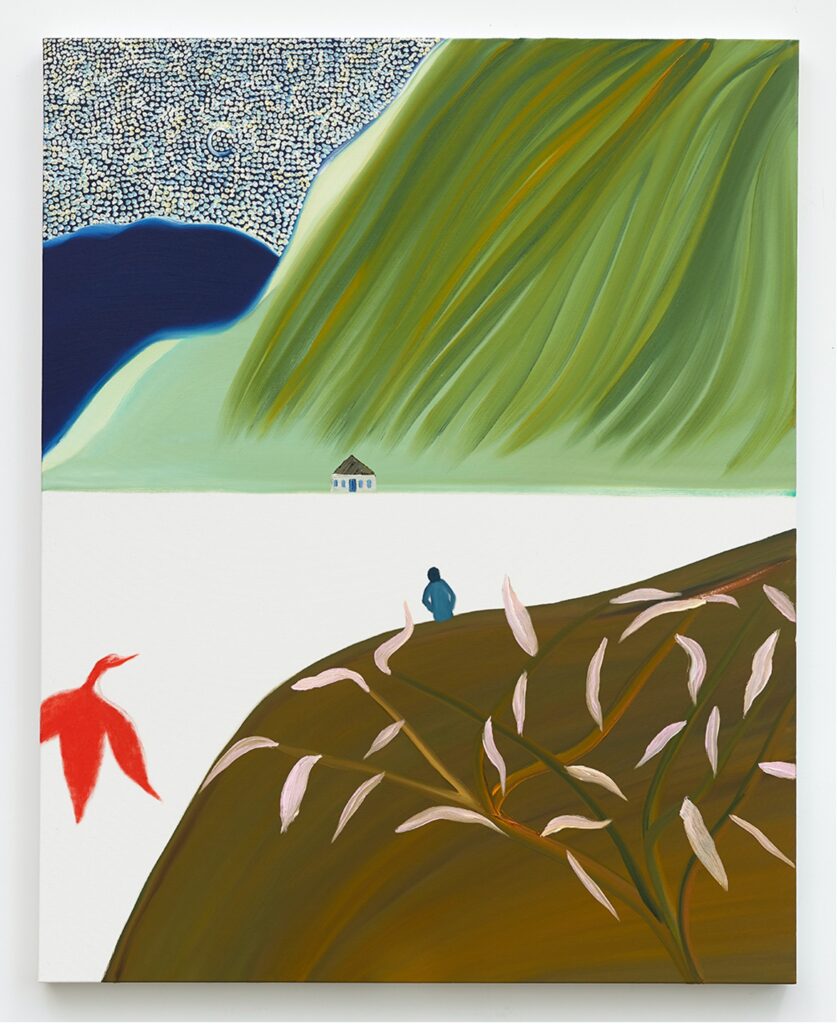

In Matthew Wong’s painting ‘See You On the Other Side’, the horizon line divides the composition into two separate, and equal, spaces. It seems impossible for the figure to traverse the white abyss. For Wong, irreconcilable distances evoke a sense of perpetual isolation and the longing to be elsewhere. Perhaps this reflected his mixed Chinese/American heritage. Certainly his painting melded Western and Eastern traditions.

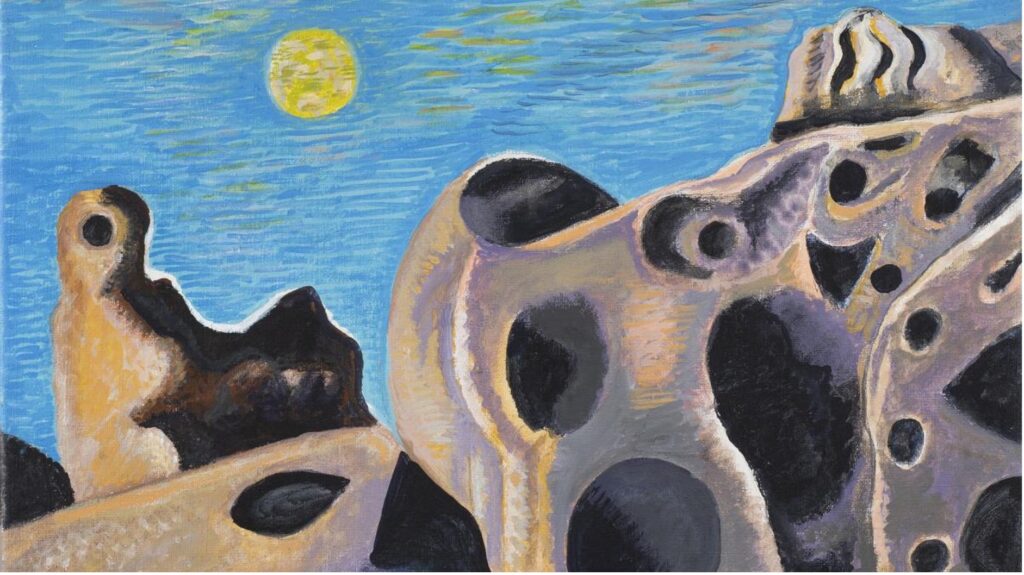

‘I have spent my whole life in revolt against convention, trying to bring colour and light and a sense of the mysterious to daily existence. One must have a hunger for new colour, new shapes, and new possibilities of discovery.’ Eileen Agar certainly transformed the everyday into the extraordinary. Her unique style nimbly spanned painting, collage, photography, sculpture and even ceremonial hats. She had a talent for overlay and juxtaposition. She enjoyed working from photographs of seaside rocks as she saw the natural world as anthropomorphic.

This short Tate video gives revealing insights into her ways of working.

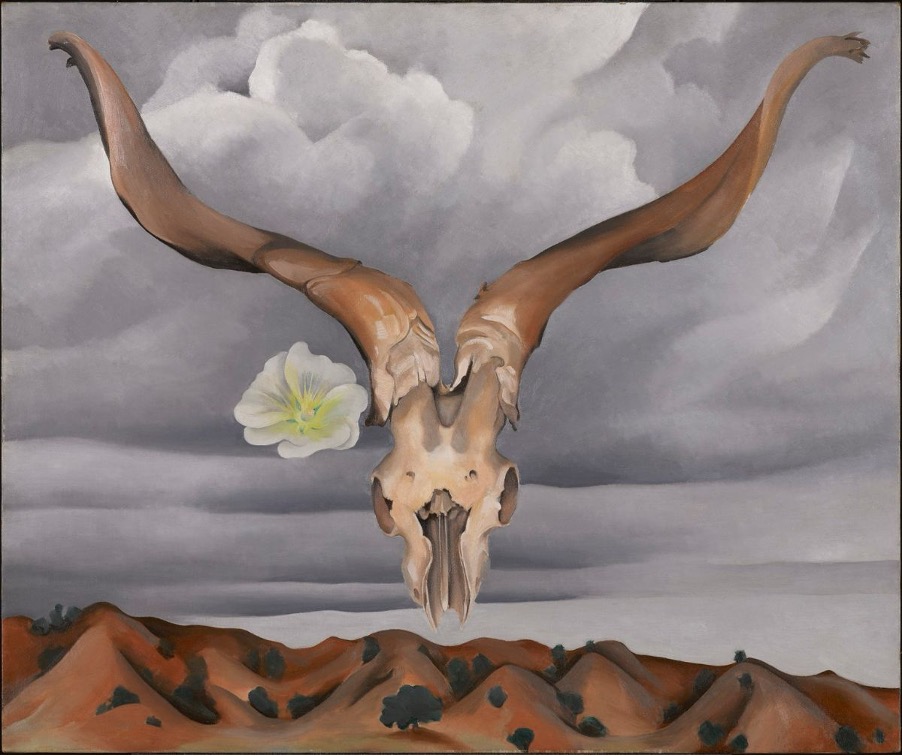

Georgia O’Keeffe considered “it is only by selection, elimination and emphasis that we get at the real meaning of things.” Most years, she worked partly in New Mexico, where she collected rocks and bones from the desert floor and made them, together with the distinctive architectural and landscape forms of the area, subjects in her work.

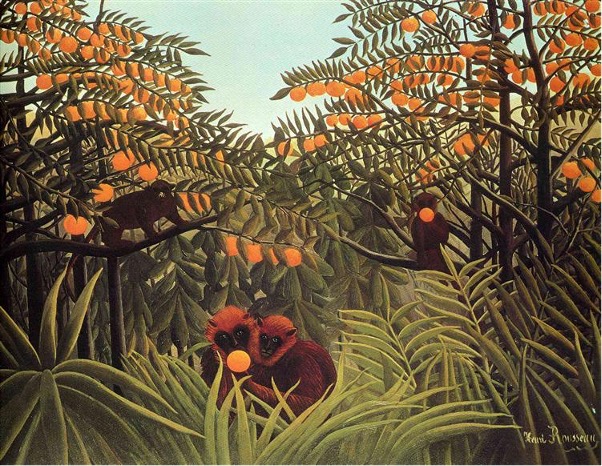

Henri Rousseau (Le Douanier) is celebrated for his visionary jungle paintings. They captivate us with the lushness of their plant and animal life, painted with incredible detail and precision. Extraordinarily, the artist never saw the tropical scenes which he brought so much to life, as he never left France. His exotic jungle paintings are the fantasies of a city dweller, constructed from visits to the zoo and botanical gardens, from postcards, books and from Rousseau’s vivid imagination. These jungles have intrigued people for decades, offering a dream of escape from humdrum reality to a savage and yet enchanting realm.

While working as a barber in Jamaica, John Dunkley maintained his artistic pursuits. Active for little more than a decade before his early death, his output as a painter was small but reveals a unique and compelling aesthetic. Most of the paintings are imagined landscapes replete with hidden symbolism. The surfaces are delicate and tapestry-like. Fantastic vegetation, bare truncated branches, small mammals, crabs, birds and often spiders inhabit gloomy woods. Human presence is only implied by an occasional house or pathway. In “Back to Nature” the path, impressed with footprints, encircles an imagined heart-shaped grave, almost certainly his own, with images taken from commercial catalogues. Here his granddaughter talks about him.

A pioneer of both Dada and Surrealism, Max Ernst channelled individual and societal anxieties into his fantastical paintings, prints, drawings, collages, and sculptures. The sense of a vast, personal mythology transcends all of his work. The artist used automatism to tap into his subconscious which yielded figures that blend elements of humans and animals. He served in World War I and his work partly reflects his horror at the cataclysmic upheavals of the first half of the last century.

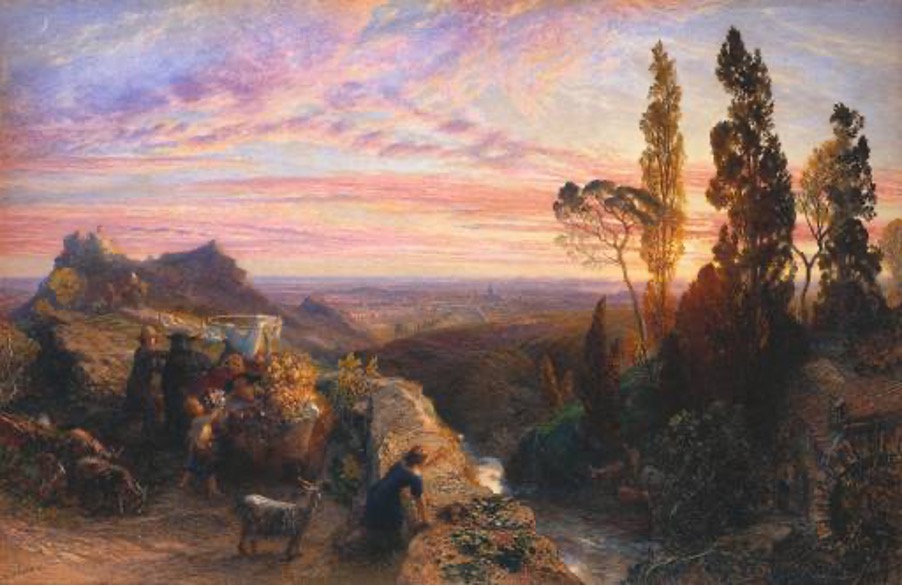

A devoted disciple of William Blake, Samuel Palmer produced imagined, highly stylised landscapes based on rural southern England. This he depicted as a demi-paradise, mysterious and visionary, often shown in sepia shades under moon and star light. Later in his career he was able to visit Italy and produced more saleable, romanticised paintings based on sketches he made there. This short video shows many more of his mysterious and otherworldly drawings and paintings.