In 1913 Marcel Duchamp (above) had the “happy idea” of fixing a bicycle wheel to a wooden stool and watching it turn. By taking two common, practical objects and uniting them in one new object they became redundant, but simultaneously reborn as a single new work with no pragmatic use, but many new possible interpretations and connections. Click here if you would like to read more about Duchamp’s readymades.

German artist Max Ernst, sometime dadaist and surrealist painter and sculptor, used collage to transform our perceptions of common objects. He was often inspired by dreams in which objects were free to change into completely different things. In the image above, an upturned beetle becomes a steam boat whilst the ship’s telescope becomes the mast, and a fish floats by, like a hot air balloon or aeroplane. His fellow surrealist, Salvador Dali, below, was intrigued by the way the accepted rules of nature could be subverted in dreamland. These limp clocks appear as soft as overripe cheese – “the camembert of time” in Dalí’s phrase. Here time must lose all meaning and permanence goes with it. Ants, a common theme in Dalí’s work, represent decay, particularly when they attack a gold watch.

Long car rides with her Vet father through the Yorkshire Dales gave Barbara Hepworth plenty of early inspiration. The ever-changing, weather-beaten rocky outcrops provided lifelong source material for her work. Though concerned with form and abstraction, Hepworth’s art was primarily about relationships: not merely between two forms presented side-by-side, but between the human figure and the landscape, colour and texture, and most importantly between people at an individual and social level.

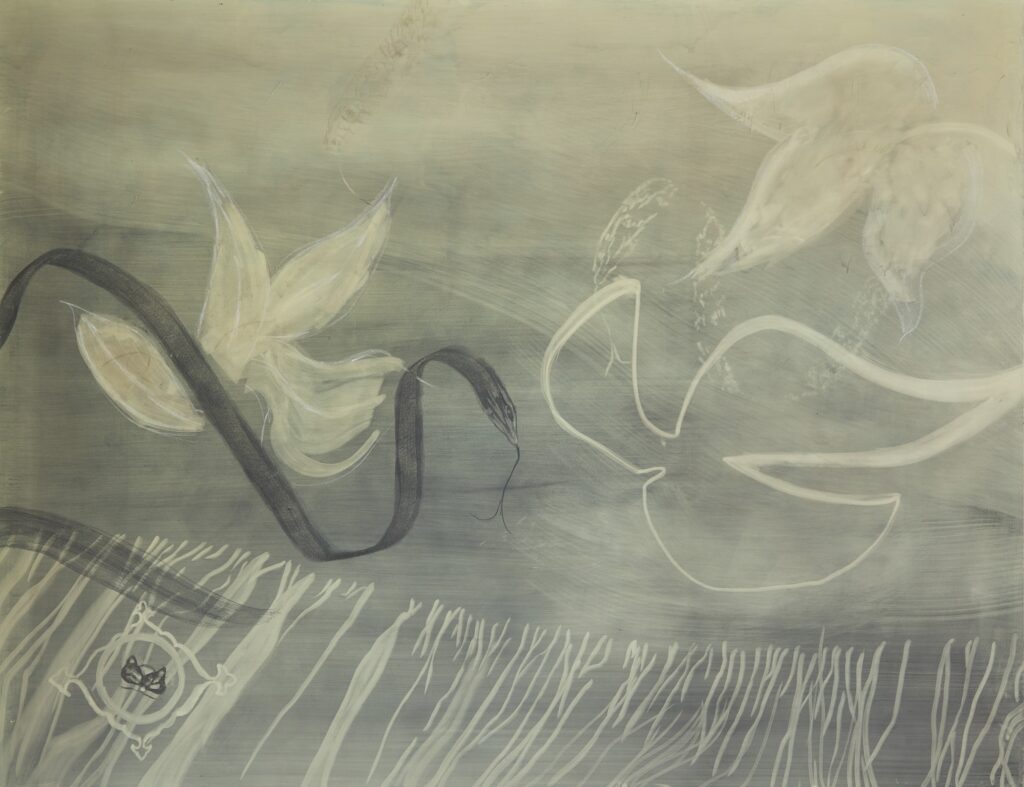

Contemporary artist Zeinab Saleh works with painting, drawing and video. Using everyday experiences, home video footage and music, Saleh’s work offers a glimpse into a past world and places personal histories at its core. In her recent work, forms and figures emerge as layers of charcoal are removed from the canvases, revealing a depth of field behind masked areas and silhouettes. Her animal and plant subjects appear in muted colours, and fluid lines like apparitions in the shrouded atmosphere of a dream or memory. In this 4 minute video, Saleh talks about her work.

Working entirely alone, Cindy Sherman has used photography for decades to assume multiple female personae that comment on the many and varied ways in which society views women and how women see themselves or wish to be seen. With an arsenal of wigs, costumes, makeup, prosthetics, and props, Sherman has deftly altered her physique and surroundings to create a myriad of intriguing tableaux and characters, from screen siren to clown to ageing socialite. By over-dramatising stereotypical and clichéd imagery of women, she renders it critically perceptible – commenting both on the construction of identity and the strategies of media representation. If you have an hour to spare, this BBC4 programme about Cindy Sherman is very informative.

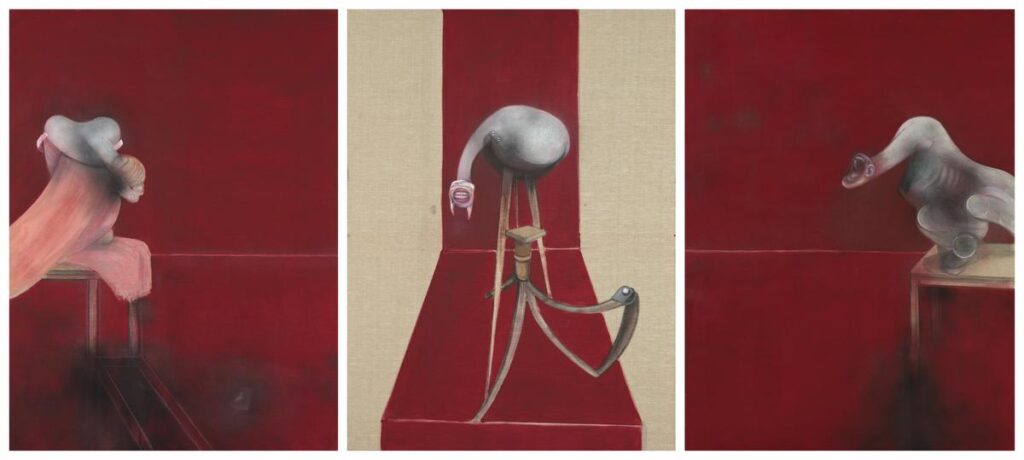

Francis Bacon brought new emotional intensity to the painted figure by representing his subjects—be they friends or mythological figures—as contorted, fleshy, emotionally open masses. He sought to reveal, in all its complexity, what was behind the human facade. “I would like my pictures to look as if a human being had passed between them, like a snail leaving its trail of the human presence…as a snail leaves its slime,” he once said. Indeed, Bacon’s paintings pulsate with the dual energy of human suffering and ecstasy. Bacon’s show at the Royal Academy runs until 17th April.

Although her fluid, colourful painted canvases attracted the most attention, Helen Frankenthaler transformed her painting style into an abstract printing style, counter-intuitively, using very precise and traditional Japanese methods. Frankenthaler experimented with this very challenging printmaking technique, involving carved wood, which she would come to master and pioneer. “She saw herself as a painter, but she kept going back to printing,” says Jane Findlay of the Dulwich Picture Gallery where Frankenthaler has an exhibition of prints. Her prints achieve the same sense of effortless spontaneity as her paintings – a style the artist is best known for, despite her careful and controlled methods. “A really good picture looks as if it’s happened at once,” Frankenthaler once said. “It’s an immediate image. For my own work, when a picture looks laboured and overworked … there is something in it that has not got to do with beautiful art to me.” Her Dulwich Picture Gallery show can be viewed here.

And finally, although principally a painter, Henri Matisse also made sculptures, including this series of four bas reliefs of a nude woman’s back. Produced gradually over 20 years they provide a record of his increasingly abstracted style and thinking. He progressively simplified the curving, moving human form to end up with a still, pared-down rectilinear composition.