This lesson overview was written to coincide with the excellent Giorgio Morandi exhibition at the Estorick Collection in 2023.

Morandi is best known for his powerful, but small, enigmatic still life paintings, though he was also a great printmaker. When he died in 1964, his preoccupation with still life as a subject was out of fashion, but today, he is widely recognised as one of the most significant artists of the last century.

This short video gives a good overview of Morandi’s life, work and studio.

Deeply affected by his experiences in World War I and by subsequent developments in Italy, he lived in Bologna all his life, mostly living and working in a modest apartment with his three sisters. His distinctive, mature style, is renowned for its masterful treatment of light, tonal subtleties and exploration of what a still life can represent. The following three paintings from the Estorick exhibition illustrate different aspects of his style, character and approach to making art.

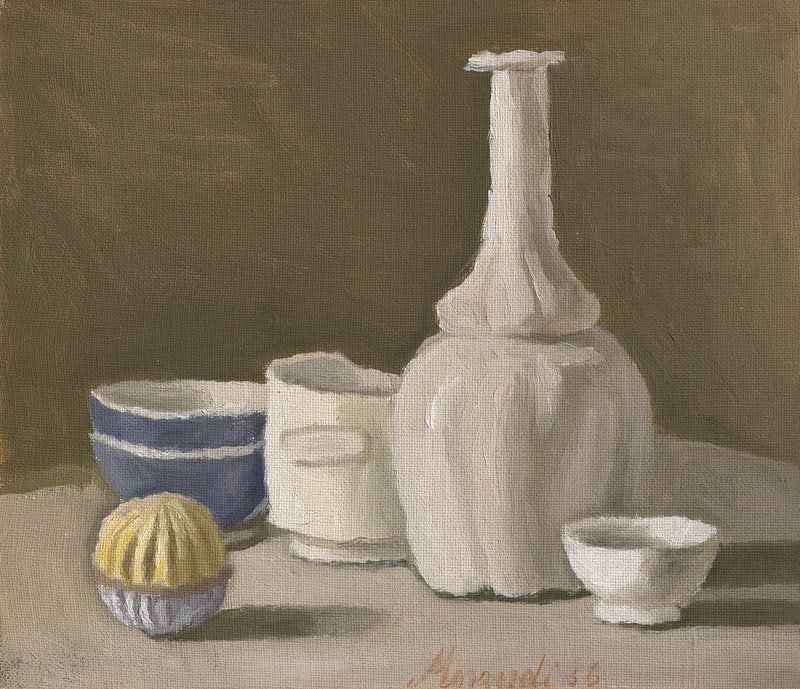

Morandi peopled his austere, pared down spaces with simple, everyday objects such as small vases, bowls, bottles and jugs, which he covered in paint to remove unwanted patterns and colours, and achieve the harmonies of colour and tone that he needed for his paintings. It’s possible to spot the same objects appearing in different works, having been repainted in different colours and tones, in order to perform different roles in new compositions.

His objects often appear to me like individual human figures of varying statures, arranged in a huddle or small crowd, though sometimes in a straight line, perhaps posing for a photo. Or alternatively, as in the painting Natura Morta of 1936, in a shallow curve of four overlapping figures focusing in on the fifth and smallest figure (actually a lemon squeezer), perhaps to hear what the latter has to say.

He uses cool, earthy browns and greys, occasionally yellow or blue, but always dull, muted colours. His short paint marks remain visible giving his figures uneven, trembling edges, perhaps suggesting the irritable, jostling movement of individual human characters.

Five years later, during World War II, Morandi had met a very influential friend and collector, Luigi Magnani, from whom he accepted a rare commission to paint a composition of complicated, rare and fancy, musical instruments. Morandi did not like being restricted by commissions nor did he like the subject matter requested. So he instead chose an old mandolin, small trumpet and toy guitar found in a flea market. He balanced them precariously in an elongated pattern of curves and straight lines, solids and voids. The result was Still Life (Musical Instruments) of 1941, in which the instruments do not seem to be artfully arranged but merely piled up as if in storage. Each object is stubbornly itself, while constrained, even crushed, by the position of the others. The overall abstract form seems as important as the rendering of individual instruments. It is very much a Morandi, and although Magnani remained a lifelong friend and major patron, he never again tried to influence what the painter painted.

A year after painting the musical instruments, Morandi produced a study of a vase of roses entitled, Flowers. The grey vase is placed centrally but not shown in full so that the emphasis is clearly on the heavy-looking, wilting mauve flower heads. Or bowed human heads? Very little in the way of enlivening, complimentary green stems or leaves are shown. This rather sad spectacle perhaps reflected the ominous, turbulent events unfolding in Italy at the time.

If you have a little more time, this recording of a zoom webinar lead by American contemporary artist and teacher Jordan Wolfson is a great way to learn more about Morandi and his work.

You might also like this 5 minute video of Alice Mumford musing on the beautiful inside/outside still lifes of Morandi contemporary Winifred Nicholson.