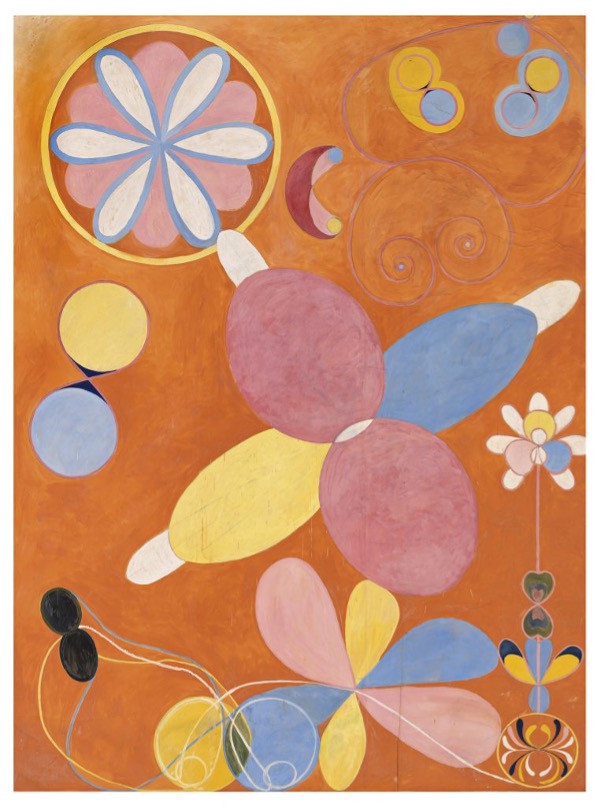

Hilma af Klint

The paintings of Swedish artist Hilma af Klint delve into spirituality and supernatural worlds. Beginning as a skilful painter of landscapes and botanical studies in the 1870’s she began participating in the then popular entertainment of séances, studying theosophy after the death of her sister in 1880. Understanding of the physical world was expanding to include invisible forces, such as electromagnetism and in X-rays. In this context, to many people at the turn of the 20th-century, communication with restless spirits and other unseen forces seemed absolutely plausible.

Af Klint believed that some of the spirits she contacted handed down commissions for paintings representing transcendent aspects of humanity in relation to the earthly and astral planes. As a result she produced a cycle of 193 paintings for the central project of her career: The Paintings for the Temple.

Completed in 1915, this cycle is made up of groupings each exploring distinct themes such as spiritual evolution and the passage from life to death. Painting No.4 Youth, shown above, is from the series the Ten Largest made in 1907. These 3 metre-high canvases evoke the cycle of human life.

Her use of colour verges on the psychedelic. The feminine is represented by the colour blue and the lily, the masculine by yellow and the rose; numerals and lettering are scattered across the paintings as though annotating scientific diagrams. Abstract motifs included spirals, interlocking circles and colour wheels.

Af Klint described how she made the works. “The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.”

This short Tate video is a very good introduction, then this longer Serpentine galleries video gives a fuller picture.

Giorgio de Chirico

Contemporary with af Klint, the Italian Giorgio de Chirico was producing paintings both eerie and mysterious which prefigured surrealism. His Mystery and Melancholy of a Street of 1914, shown here, is a sombre and forbidding painting suggesting an imminent encounter between a girl running with a hoop (the only moving things) and a statue that is present only through its shadow.

The girl is heading towards the source of bright light behind the building on the right which illuminates the arcades on the left.

De Chirico intentionally uses two contradictory vanishing points, thereby dislocating the composition and disorientating the viewer. The diagrammatic, enigmatic wagon parked in the shadows, its rear doors open, suggests an unwitnessed incident – perhaps an escape (of animals?).

This juxtaposition of light sources and perspectives enabled de Chirico to create a sinister and impossible universe where elements never quite align or converge. de Chirico subverts our notion of the typical European city square as representing the familiar, traditional and orderly heart of our communities.

To learn more about de Chirico’s life and work click here, and here.

Martyn Cross

The young contemporary Bristolian painter Martyn Cross creates his own worlds. Each work begins in reality, with recognisable limbs and elements of landscape, which he gradually transforms and fuses together into uncanny scenes. The resulting paintings have a naive, primitive feel with an element of comic fun and mischief alongside mystery and ambiguity.

Cross surrounds himself with eclectic things that inspire him; images of medieval wall painting, old English churches, the work of Forest Bess and William Blake, science fiction books and walking sticks. These sources re-emerge subconsciously as recurring motifs – billowing clouds, tumbling waterfalls, oversized pointing fingers and bright suns. Biomorphic landscapes speak of mythologies, but in Cross’s paintings the narratives are knowingly ambivalent. His works are simultaneously familiar and mysterious, quiet and epic.

His oil painting shown here: A Tomb for Immortal Ascension of 2022, exemplifies his current style. His dabbed, layered application of oil paint, using an earthy, cave-painting range of colours, creates a hazy, humming stillness. Sanding and scratching of surfaces results in a lived-in feel. Deliberately hard to place in history, there is a timelessness to Cross’s paintings, reminiscent of unearthed artefacts.

This review of his recent exhibition at Hales Gallery reveals more, and this in-depth interview is certainly worth reading too.